We used to joke in my home growing up that I was the only member of the family who could be president: I was the only one in the household born on American soil.

Earlier this year, at age 39, I began to wonder when my parents had become naturalized citizens. I had never been clear on the timeline. I was astonished to learn that my parents, along with my sister, had not become United States citizens until I was ten. Old enough to have been aware, but it simply hadn’t been of consequence to my own life or safety.

Birthright citizenship has now been deemed an urgent-enough danger as to have been among the very first targets on MAGA back-to-skool day in January. Despite the voices of reason who persist in their assurances of how “clearly” unconstitutional and unenforceable that presidential order is, here we are. What troubles me, besides enforceability, is the indelible ugliness its debate has revealed.

I feel, to my core, shaken by the notion of a world where my American citizen status might not have been automatically conferred upon me. My Americanness is intrinsic to my identity, on an unthinking, almost biological level. When I refer to Americans as “we” and “us”, it is because I understand myself to be part of an unbroken collective spanning back to our bloody birth. As much as I may have a firsthand understanding of racism as an American, this form of nationalism felt like a new, baser hostility: the idea that people question my right to exist as American at all. This hostility has always been there, I’m sure, and I’ve chosen not to see it. I’ve been so bolstered by the undeniable FACT of my Americanness, that it’s never bothered me who might judge otherwise.

When I first started writing these words three months ago, my personal misgivings felt shrill and alarmist. Privately, I could easily envision how people might begin to rationalize my own deportation — even as a citizen since my first breath, back in 1985, at Portland’s Bess Kaiser hospital. Publicly, I knew how crazy I might sound speaking that fear out loud. How it might appear to twist the narratives of migrant deportations and asylum denials to be about me, personally.

Now, it is Independence Day. Only a few short months later, and I hardly think that anyone would argue with me now for airing such thoughts. The BBL Bill (or whatever it’s called) has just passed. Private prison contractors smack their lips over ICE’s 45 billion dollar bonanza, while influencers shill prison camp merch. If I didn’t have this draft simmering while politics spiraled, I would disbelieve how quickly MAGA politicians have accelerated into public menace; how easily their lunacy would be rubberstamped by the others; how rapidly the reasonable majority of Americans have been forced to acclimate to our new political realities.

Back in 1995, my parents had been ambivalent about gaining US citizenship, mainly because of the requisite waiving of their Indian passports that would follow. This caused them to wait until my sister was nearly eighteen to take the plunge. They had been legal residents and greencard holders in the meantime, following all the rules. But the intent of undermining birthright citizenship is not about following the rules, or “doing things the right way.” The intent is to make it clear that you must prove that you “deserve” to be an American, and to make it clear who grants that worthiness. It suggests that Americanness is not earned but conferred; not to be gained, but to be gatekept.

As the case of Mahmoud Khalil and dozens of other legal-immigrant detainees makes clear (and surely more to come), a greencard is only “the right way” until someone decides they don’t like you, or what you have to say. (Perhaps my dad’s Communist undergraduate stirrings would have become a liability). Not even citizenship protects the immigrant, now. All of a sudden, it’s not just raising politically inconvenient opinions that warrants your deportation, or even denaturalization! It’s eating with your hands. It’s being a political enemy. It's a terrifyingly simple, administrative error.

The fact that I never once concerned myself with my parents’ immigration status while growing up, speaks to the climate of the 80’s and 90’s. Not a universally welcoming time for brown people in this country by any means, but one in which I felt a total lack of fear and concern around our futures. A trust that the system would support them in their journey, and a trust that becoming American was a natural inevitability. It was something that my parents could choose, and not something they needed —or wanted— to fight for. It’s not difficult to imagine that, if our family story were unfolding today, the kitchen table conversation would be dominated by this subject; my ten-year-old self would be acutely aware of the circumstances and their deeper meaning.

I have not asked my parents what their relationship is to their citizenship today. How “American” they feel, as opposed to which portion of them still feels a little “Indian” — nationalistically rather than culturally. I suspect that while they’ll always be culturally Indian, they have felt fully American for a long time. The relationship to patriotism has always been unique for immigrants. In my experience, there is no zeal for Americana quite like the new arrival’s. Many immigrants have a tendency to throw themselves with a particular intrepid, adventurous joy into customs and traditions and new experiences – it’s a phenomenon my sister and I find heart-meltingly tender when we recognize it in others now. Our parents, with zero understanding, took us camping and rafting. They signed us up for toddler swim classes, and taught us to ride bikes in the park, considering these to be supremely American pursuits. (to this day neither of my parents can bike nor swim, themselves).

For the immigrant, there’s also a steadfast belief in the systems and ideals of their adopted home; a championing of the place that has enabled them to create a good life. This belief has only in recent years been truly destabilized in my family. I for one, as a function of my upbringing, have always considered myself a patriot. I love America. One of my seemingly incongruous viewpoints as a lefty is my belief in the significance of the flag code. I don’t believe that the flag should be flown on a car until it’s in tatters; nor should it be draped over your dick in the form of swim shorts. It shouldn't be tattooed on you, nor flown unlit by night. We should treat the flag with care and respect. Symbols are important. The ideals they represent – or purport to – are important. I believed in those ideals with all my heart, even as I knew we consistently, collectively failed to reach them as a nation. There’s something of this faith that persists, despite something breaking in me this year, a crack in my foundation that was first etched on January 6, 2021.

My parents have idly questioned whether they would choose to pursue post-doctoral studies in the United States, if they had to do it all over again. There is no way to answer that question. No way to undo 45 years of life in this country. It's impossible to ask them to imagine what their lives, and children, and grandchildren, may have been like if they had chosen to build their lives in Germany, Switzerland, the UK – or in India.

It’s a question that I find difficult to face, as well; one I’d rather not spend too much time looking at head-on. I think of my sister’s children, and know that these are matters they would never think to contemplate. Their Americanness too, feels incontrovertible – unimaginable for it to be otherwise, and unimaginable for them to be considered less-than-American by others (my nieces’ proximity to whiteness, which my own son will share too, provides an extra stamp of certification).

That is how quickly national identity is cast across a half a generation. How terrifying, and tenuous it feels to know, then, that bedrock facts of identity can be so casually undone, or that family history could so easily skitter in a different path.

Our Sunday supper playlist on Assisted Living:

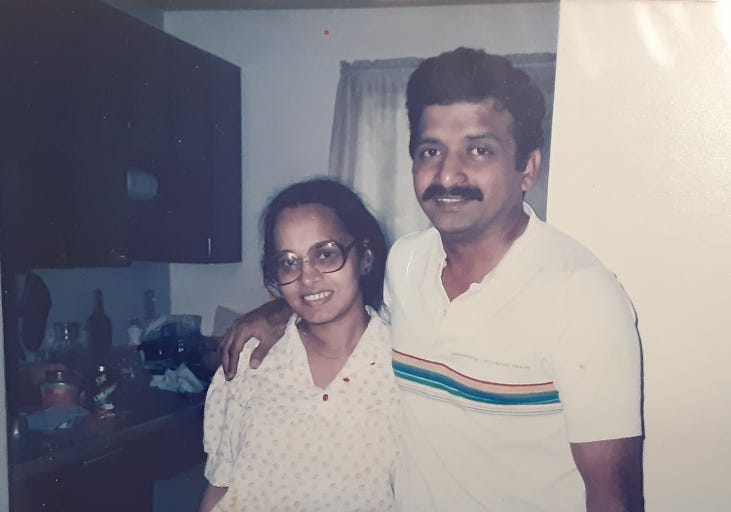

Thank you so much for sharing your perspective here - and for sharing those amazing photos! Everyone's dad really did have the same mustache in the 80s-90s huh? Maybe that's the most American thing of all!

I appreciate you writing and sharing this.

The patriotic zeal of new citizens- yes! Endearing indeed. We had the same green Dodge Dart. And the flag- crazy that so many who call themselves patriots would treat the flag with such disrespect. Technically it is actually illegal to wear the flag (on clothing, crotches, and more) or duplicate it on merchandise- yet this is a law that has always been ignored. Too much money in it, I suppose and too hard to enforce.